My oncologist has considered one of those little motivational prints hanging on his waiting room wall, with the easy statement, “Trust your instincts”. One day, fed up with the long renovation of the waiting room, I tweeted the news to the world with the commentary: “If I trusted my instincts, I'd run screaming from this place and never come back. “

I'm only half kidding. I don't want to look ungrateful for the miracles of recent medicine, without which I probably wouldn't survive. Yet a routine visit to the oncologist can feel overwhelmingly frustrating.

I sit and wait for an hour or more, stuffed with dread and stress and anxiety, while I pass the time on my phone or with a trashy magazine, until my name known as. My oncologist takes a fast take a look at my latest blood test results, normally tells me to proceed the medication I'm taking, writes me a script for an additional blood test, and provides me 4 to 6 Asks to come back back in weeks.

The final straw comes nearly 4 years after my diagnosis of stage 4 metastatic prostate cancer, after I get up to depart one other uneventful ten-minute consultation after an hour's wait.

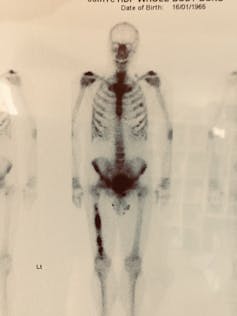

Something doesn't sit right about all of it. It's my life hanging within the balance. I've been through radiation therapy (reasonably tolerable), chemotherapy (seriously debilitating), hormone therapy (made me almost suicidally depressed) and surgery (painful but quickly over).

The writer provides.

The lack of opportunities to have more extensive conversations about treatment options, how I'm holding up emotionally and techniques to attenuate the life-altering unwanted side effects of treatment just feels improper.

I walk to the door, pause, turn and announce, “Oh, one more thing”.

My oncologist doesn't seem glad with this development. He has a waiting room filled with patients and is running an hour behind schedule.

“It's been four years now. I work so hard on this,” I begin tentatively. We're entering uncharted territory. I'm talking about my feelings and getting him to reply. Expecting, with our unspoken doctor–patient agreement is a sham until I press on.

“I follow a strict diet, exercise and meditate daily, do everything I can to support my health. Where do you think I'm going?”

I pose, opening the way in which for him to supply some soothing words of encouragement. He ponders this unscripted moment briefly, as if I've just told a joke he doesn't understand.

“About average,” he finally publicizes coldly. “Some of my patients are doing higher than you, some worse. You're average.

His response seems designed to be certain that I never again neglect to ask such an issue, or attribute the facility of a cure to my lifestyle interventions. Even if it was her sincerely skilled view, wouldn't it have saved her life by saying something vaguely positive like, “It's great that you just're being so proactive about supporting your health. “? Or a gentle white lie, even if he doesn't actually believe it: “You're doing great. Keep it up.”

Emotional distance

I even have no reason to doubt my oncologist's professionalism and deep knowledge of his chosen field. But I've been frustrated by his lack of interest in anything I'm doing to support my health, or any research or suggestions I've made as a trusted aide or Assistant treatments, all of that are quickly dismissed.

More than anything, I'd like some more proof that he cares, which will likely be hard to come back by when he sees dozens of patients every single day in roughly ten-minute intervals, lots of whom have conditions just like mine. are far more serious, most of which they'll not have the option to treat.

Justin Walpole

Scott Morrison About $200,000 was reportedly spent. On an empathy consultant on your government, but politicians aren't the one ones who need a bit of guidance on reading emotional cues. Oh 2011 US randomized clinical trial Oncologists presented a lecture on good patient communication. Half of the group were also given a tailored CD-ROM presentation to enhance their communication style, record and critique their patient interactions.

The researchers noted the anxiety and mental health challenges of many cancer patients, observing:

Oncologists often miss opportunities to reply to the patient's feelings and will as a substitute exhibit behaviors that block feelings and create emotional distance.

Dr. James A. Tulsky, writer of the report, observed:

So often patients should not satisfied with their interactions with their doctor, yet I do know that doctors care lots about their patients and actually need to indicate it. Therapists will probably want to communicate what they're feeling but may not all the time use the suitable words.

The problem here appears to be twofold. Oncologists typically fit a certain psychological profile—disciplined high achievers, in a position to process and retain highly specialized and technical information, and sometimes cool-headed in essentially the most difficult situations. Make decisions from

The writer provides.

People whose skills are geared to perform these essential tasks may not naturally be inclined to overt displays of emotion and empathy. And even in the event that they were, it could be nearly not possible to speculate deeply emotionally in each patient. Compassion fatigue is real.

But oncologists also suffer from a terrible physical and mental health profile. Several studies show that they've higher rates of tension, depression and suicide than the final population, and are worse at getting help. It is difficult to supply emotional support if you find yourself experiencing psychological distress yourself. According to An American study at the Mayo Clinic Up to 35% of oncologists suffer from burnout.

Oncologists face life-and-death decisions every day, administer incredibly toxic treatments with narrow therapeutic windows, sustain with the rapid pace of scientific and therapeutic advances, and must provide palliation and A effective line must continuously be walked between managing the treatment and adding toxicity. Personal distress brought on by such work-related stress can manifest in quite a lot of ways, including depression, anxiety, fatigue, and reduced mental quality of life.

A 2019 study found that 300 doctors die by suicide every year in America..

The stigma of depression runs deep within the helping professions, and particularly in medicine. Although burnout is recognized in oncology, other stigmatized mental health facets of clinical practice – depression and suicide – are rarely recorded or discussed.

To compound the issue, oncologists are sometimes reluctant to report mental health problems, considering it a possible blot on their profession record. “Doctors are trained to be perfectionists. They are trained to never show any weakness, and they see mental health issues as weakness,” Anthony Elbeck, MD, University of Washington. Professor of Medical Oncology on the medical center, told HemOnc Today. An online journal of oncology and hematology.

yet one more American studies 30% of oncologists were found to “drink alcohol in a problematic manner”, and as much as 20% of junior oncologists used hypnotic drugs or sleeping pills.

2016 Australian Qualitative Study Workforce sustainability in oncology Paints an analogous picture.

The researchers conducted in-depth interviews with 22 medical oncologists at various stages of their careers and concluded:

There is considerable concern that increased patient volume and intensity – as has been shown in other studies – will result in each poorer outcomes (e.g. burnout), and their patient care. and when it comes to the standard of support they expect from their medical oncologists.

As one early profession cancer specialist put it:

I believe it's worthwhile to have the option to commit to that point. [to patients] To do an efficient job and if [treatment] It becomes an exercise in ticking boxes … it dehumanises the connection, which I discover a struggle … when there's not time to see everyone and you could have to rush them out, I This seems to eliminate this essential a part of the patient physician's motivation. .

Ironically

In my very own case, I finally took the recommendation of the wall print in my oncologist's office and trusted my instincts.

I fired my oncologist and located a brand new one open to discussing my lifestyle strategies, expressing compassion and concern for my mental struggles and quality of life with my cancer.

Does it strike anyone else with the identical sad irony that one of the serious health problems of our time is presided over by a really unhealthy doctor? The current model of cancer care doesn't serve anyone's best interests, doesn't address complex patient needs and demands a cruel tool on clinicians. We are all – patients and doctors alike – dying within the war against cancer.

Leave a Reply