August 31, 2023 – This is a real story.

I went to highschool with a man named Frankie. He was a hothead – at all times in trouble because he couldn't control his temper. He was rude to teachers, got into fights – perhaps even had a number of run-ins with the law. We called him Frankie the Fuse, but never to his face.

Fast forward 20 years. I'm at a minor league baseball game and across the aisle is none aside from Frankie the Fuse. He looks at me, I take a look at him, and shortly we're fast friends again. By the top of the sport, we've made plans to play golf the next weekend.

And so began the agonizing and ultimately disastrous renewal of our relationship. Although Frankie was approaching 40, his fuse was now not as strong. During our first round of golf, he botched a chip shot, set free a string of curses, and threw his wedge right into a pond. On other outings, he bent a 5-iron around a tree and broke the windshield of our golf cart together with his fist. When we played with golfers we didn't know, I had to tug them aside beforehand and warn them about Frankie's outbursts.

Eventually it got so bad that I needed to make up excuses for his calls or emails until he got the hint.

The age of idiots?

Everyone gets frustrated, upset, and indignant sometimes. It's even normal to scream, swear, throw things, or smash a pillow now and again. But some people, like Frankie, can get uncontrolled.

Based on news reports and my social media feed, the variety of “Frankies” on the earth appears to be multiplying. Perhaps we're getting angrier as a society, or perhaps we're simply less inhibited about behaving.

We've all seen videos of road rage, of somebody yelling at a flight attendant on an airplane, or of an indignant customer raiding a fast-food restaurant.

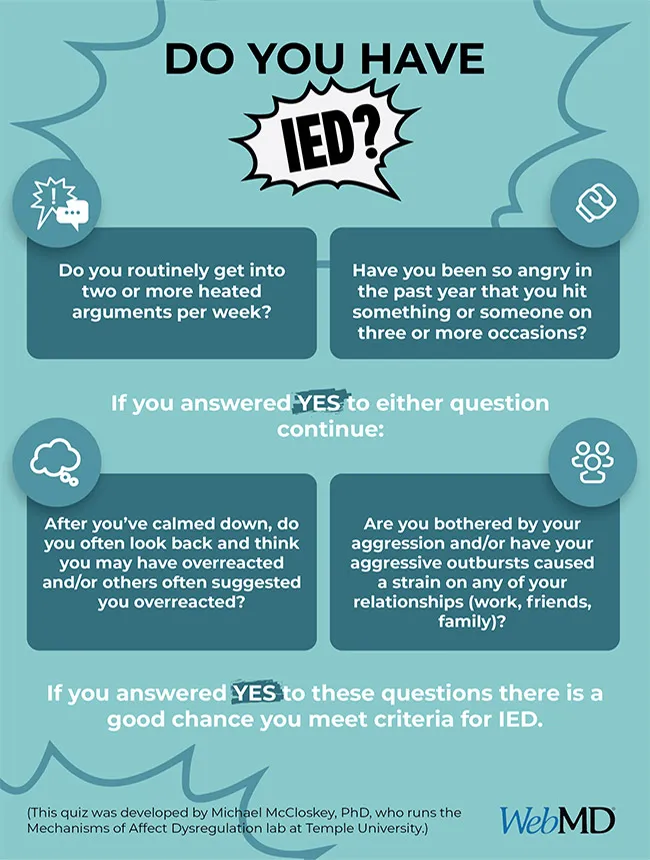

I used to think these people were just idiots, but it surely seems that these outbursts of anger might be attributable to a little-known mental disorder called Intermittent Explosive Disorder (IED), and victims might not be aware that they've it or know that it could actually be treated.

Over the previous few a long time, science has repeatedly clarified the IED theory, and in the newest version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM5), There's an entire section on it. (The undeniable fact that it has the identical acronym as “improvised explosive device” is an unintentional but glad coincidence, experts say.)

The disorder is greater than just “getting angry quickly,” says Dr. Michael McCloskey, a professor of psychology and neuroscience at Temple University and a number one IED researcher. “When they get angry, they react aggressively – they scream and yell, break things and get into physical fights.”

This response is disproportionate to the trigger, he said. “For example, if someone tries to hit you and you hit back, that's not an explosive device. But if someone says they don't like what you're wearing and you hit them, that could be a clue.”

According to Emil Coccaro, MD, associate director of research within the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Health at Ohio State University and a world-renowned expert on IED, roughly one in 25 Americans (that's 13.5 million) are affected by the disorder.

“We don't have any data on whether the number is increasing or not,” he said. “But life has obviously become faster, people feel more stressed, and that could be contributing to this.” Or we're simply seeing more incidents because everyone has a mobile phone now, or the DSM5 Entry facilitates diagnosis.

About 80% of patients with IED aren't treated, Coccaro said. (As far as I do know, Frankie never sought help for his outbursts and possibly never heard of IED. But after I described his behavior to experts, they agreed he probably has IED.)

The Science of Anger

Two things occur within the brain that trigger such a response. Coccaro points out that aggression is an evolutionary necessity. We need a defense mechanism to guard ourselves from threats. So when a threat is perceived, “the amygdala, the reptilian part of our brain, turns on to trigger either a fight or flight response,” he explained. “But in people with IED, the amygdala reacts faster and more strongly. Its fuse is shorter.”

“Overly aggressive people tend to have lower levels of serotonin in their brains,” Coccaro said. This naturally occurring chemical messenger counteracts aggression, amongst other things. “Think of serotonin as your braking system,” he said. If your brake fluid levels are low, you'll be able to't stop.

People with IED don't plan their outbursts. They just occur. Nor do they use them to control or intimidate others. (That can be antisocial or psychopathic behavior.) Rather, they simply misperceive threats after which cannot control their response to those threats. They freak out.

But they're well aware of their behavior. Even in the event that they don't apologize directly, “they feel the impact it has on their family and friends and how it alienates them,” says McCloskey. “It's not something they enjoy. It's upsetting.”

IED is barely more common in males. Men are inclined to be more physically aggressive, while women with IED usually tend to be verbally aggressive. IED is most typical in teens, 20s, and 30s, after which the danger decreases with age, although the danger of an outbreak at all times stays.

Research has not yet determined whether certain occupations or socioeconomic conditions make people more prone to own explosive devices, but genes actually can. “The more severe the aggression, the more genetic influence there is on that aggression,” Coccaro said. That influence is less strong for verbal aggression (mid-20%), stronger (mid-30%) when hitting something, and strongest (mid-40%) when hitting others.

Education also plays a job. It will not be unusual for individuals with IEDs to grow up in broken homes with violent parents.

Another possible reason behind IED is inflammation, which also plays a job in other behavioral disorders resembling depression, schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. “There's some research in cats that shows that if you put inflammatory molecules in their brains, they become more aggressive,” Coccaro said. IED may result from a head blow that damages the temporal lobe of the brain, where the amygdala is positioned.

We don't yet know whether anger outbursts that go untreated can worsen. In other words, can years of anger culminate in a very violent outburst – toward others or toward oneself?

“We don't know if it progresses that way,” Coccaro said, “but we do know that about 20% of people with IED attempt suicide or commit some other form of self-harm.” And alcohol or drugs could make people more vulnerable to provocation and their outbursts more uncontrollable. IED can result in domestic violence, however the experts we spoke to don't link it to mass shootings. Those are planned, while IED happens spontaneously.

get help

Fortunately, there are methods to cope with IEDs.

The first is cognitive behavioral therapy, the classic type of psychotherapy for treating general behavioral problems. “We teach patients how to recognize whether their perception of an anger-inducing situation is based on fact and then how not to react aggressively. This type of therapy has been shown to reduce aggression by 50% or more within 12 weeks,” McCloskey said.

The second treatment method, which might be combined with the primary, is drug treatment. “Serotonin reuptake inhibitors have been shown to be effective,” said Coccaro. These antidepressant-type drugs improve the behavioral braking system mentioned earlier. Antiepileptic drugs also appear to have some profit.

McCloskey's lab can also be working on a latest computer intervention that shows promise in treating aggression. It teaches patients coping skills by showing them threatening and non-threatening words or pictures on a screen. “Technology could make treatment more accessible and engaging,” he said.

These treatments require that the patient recognize (or be convinced) that she or he needs help. As with alcoholism or drug addiction, this hurdle will not be easy to beat.

“We all have our defense systems,” says Dr. Jon Grant, professor of psychiatry and behavioral neuroscience on the University of Chicago. “It's easier to blame others than ourselves.”

And when you encounter someone who's indignant? “Don't tell them to calm down or try to reason with them. Just walk away and get to safety,” he said. “And don't film them. That's insensitive. There's no reason to ridicule or embarrass them. In fact, they might get even angrier if they see you filming them.”

But later, after they've calmed down, Grant recommends talking to them. “Look, you just threw your club in a pond and gave me a good scare. I'm not going to play golf with you anymore if you keep doing that.” Season the ultimatum with compassion. Say you ought to higher understand why they're reacting that way and ask when you may help.

“Most people think it's just bad behavior and the person who does it needs to change their mindset,” Coccaro said. “But the truth is there's a lot of biological evidence that IEDs are a real thing. It's not just a matter of mindset.”

“It takes a brave person to admit to this disorder,” Grant said. “Although many athletes, celebrities and politicians probably [have] there is no one who acts as a figurehead.”

Depression inspires compassion, but aggression makes us fearful, Grant said. “And when someone admits to abuse, we robotically want to provide our attention to the victim, not the perpetrator.”

Should we give vent to our anger?

You may have heard of rage, angry, or smash rooms. These are commercial places where you can destroy computers, furniture, mannequins, or pretty much anything you want for a fee. The theory is that it's better and safer to vent your anger in a controlled environment than to let it out in the real world.

“If you don't have an aggression problem, it's probably just fun,” McCloskey said. “But when you do, it's probably not an efficient technique to cope with it. It just reinforces the way in which you approach an issue by reacting aggressively.”

“There's also an idea called 'acquired skill,'” he continued. “When you grow to be more comfortable with a behavior and it becomes a part of your repertoire, you're more prone to do it.”

McCloskey stressed that anger is a normal human emotion and that expressing that anger (within limits) can be healthy. Occasional small acts of excessive aggression are normal. But if it goes beyond that, get help.

“The interesting thing about all of this,” McCloskey said, “is that individuals with depression or anxiety say, 'Oh, that's what I'm being treated for.' But individuals with IED are inclined to think, 'I'm just an aggressive person and there's nothing you'll be able to do about that.' That's just not true.”

Leave a Reply